Black hole rendering

This week's Weekly Creative Coding Challenge theme is "shadow math." I thought I'd take the time to try to (approximately) render some black holes in a shader! Here's how I chose to approach it, in a not physically-based, but perhaps physically-inspired manner.

Looking at star maps

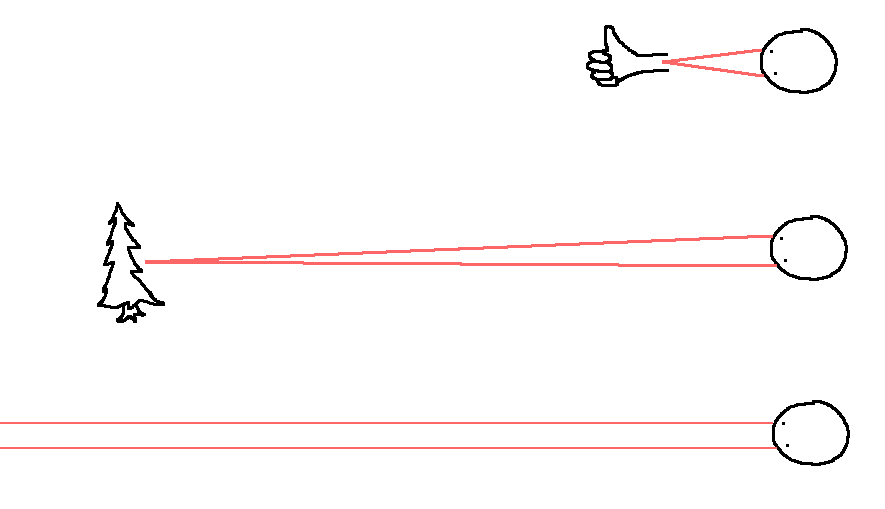

So there's this thing called parallax. When you hold your thumb out in front of your face, and then alternate between only opening your left then your right eye, you'll see your thumb jump. That's because your eyes are in different spots! The angle from each eye to your thumb is different.

If you do the same thing when looking at a tree in the distance, the same thing happens, except it jumps less. That's because the tree is farther away, making the angle difference between each eye a little smaller. If you stare at stars, wayyyy off in the distance, the angle difference is so small that it's basically nonexistent: the lines from your eyes to the star are basically parallel.

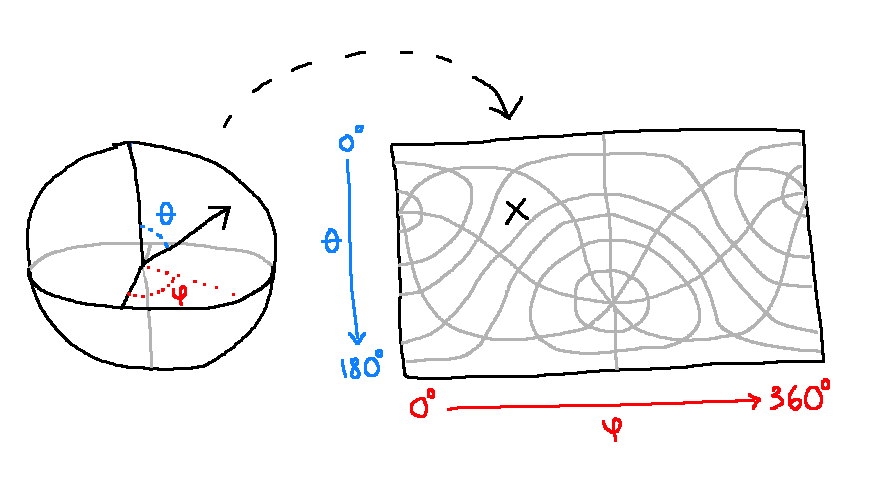

When you're rendering far away things like that, you can pretty much ignore where the camera is, and instead only look at the direction in which it's looking. The direction can be described with two angles, which can be mapped to an x and y coordinate on an image.

And, thankfully, the users of /r/blender have graciously given me a CC0-licensed rectangular projection looking at the crab nebula so that you don't need to see any more of my freehanded grid lines.

This is the basis for our shader! For each pixel in the final image, we just see what direction we're looking, and grab the color from the corresponding point in an image of space. So far so good!

Will it bend?

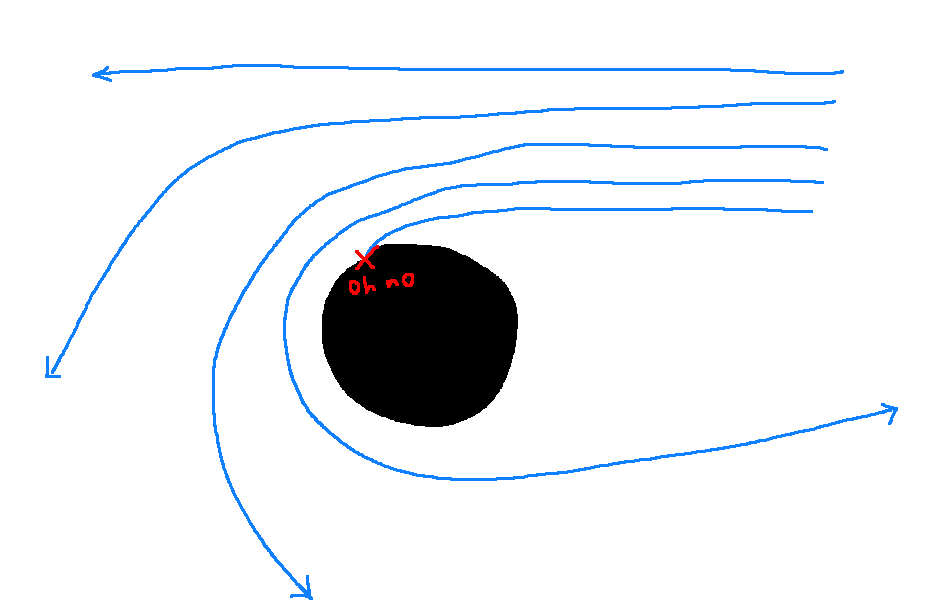

Normally, light travels in a straight line, but the funny thing about black holes is that they've got so much mass that they bend light. The closer the light comes to the black hole, the more force it's under, and the more it bends. Sometimes this causes the light to fling around the outside of the black hole and end up pointing the opposite direction that it started from. If it comes fatally close, it spirals in and never leaves.

In a proper simulation, one would use actual physics equations to calculate the trajectory of the light rays. That sounds like it takes a lot of effort, academic rigor, and GPU cycles, so I opted to take a more artistic approach of observation and imitation. It looks light the light ray rotates towards the black hole, and the angle of rotation increases the closer the ray is to the black hole. As it gets close, it turns around to face the way it came, plus some. At some threshold, the light gets sucked in and doesn't leave.

Probably there's a point before it gets sucked in where the light actually goes into orbit and it goes around an infinite amount of times? I don't know for sure, but I'm an engineer, so I can make confident statements about fields I know little about. In any case, I've opted to ignore that particular detail, and came up with a formula that loosely approximates this effect:

// Get a (very loose) number between 0 and 1 representing how close the ray is,

// where 1 means "pointing right at it"

closenessToBlackHole = map(angleToBlackHole, 0, 360, 1, 0)

// Make the closeness number have a steeper falloff so the distortion gets bigger

// really fast near the black hole

closenessToBlackHole = pow(closenessToBlackHole, 6)

// If the closeness was 0, there's no rotation. Otherwise, it proportionally gets

// rotated more and more by a very unscientific formula

rotation = closenessToBlackHole * (180 + angleToBlackHole)

// I arbitrarily picked an angle under which I just say it gets sucked in, at which

// point I render black.

pastEventHorizon = angleToBlackHole < 10

I've also opted to add some glow around the black hole itself to make it pop. There is no basis in physics for this. I justify myself to no one.

How does it compare?

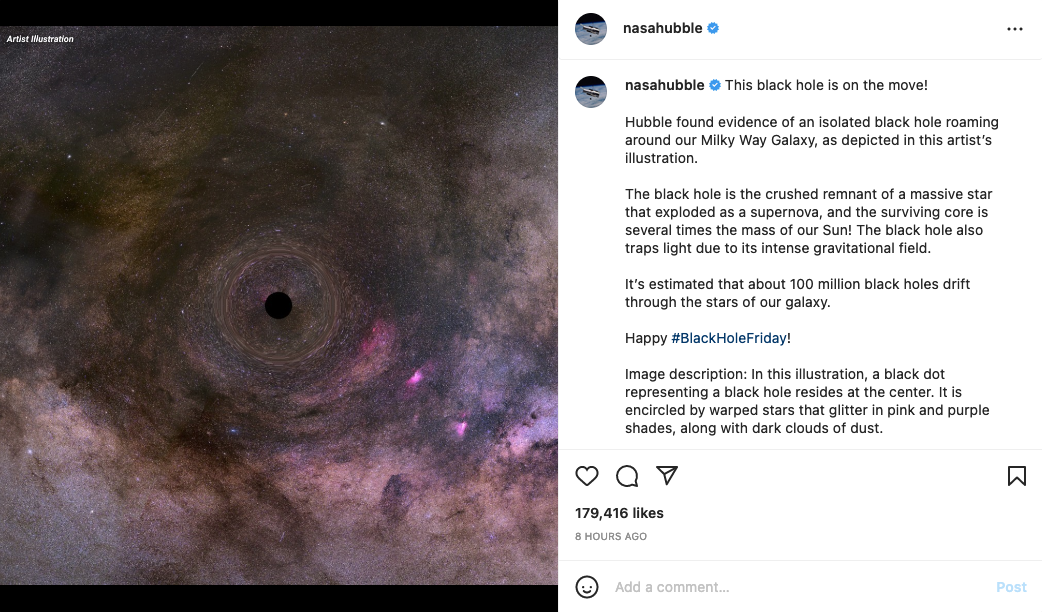

If you render it out, it looks like this:

You can see a distortion ring a distance out from the event horizon (the black area.) You can see stars moving one direction across the outside of the ring, and the opposite direction on the inside. This is, I think, the threshold at which incoming rays get turned around. That seems to follow from the loose mspaint diagram from earlier!

As confident as I was just based on output, I stumbled across some more confirmation. A few days after writing the code, I saw that the NASA Hubble Space Telescope Instagram posted a rendering of a black hole. Other than the lack of the obscene amount of glow I added, it looks surprisingly similar!

But is it cinema?

I decided that, to maximize the impact of my sketch, I wanted it to leave the realm of real physics even farther behind. I wanted it to feel more dramatic and immersive. In reality, if you move the camera, the circle of distortion should stay a circle regardless of the angle. However, I wanted it to feel a little more visceral, like you're going around a big, physical object, and ironically it feels more physical if I made it less physically-based and add perspective distortion where none should exist.

I made the camera tilt, skewing all the incoming light rays with it rather than rotating them. This causes it to look like you, the viewer, go through the ring like it's a big celestial hula hoop. To me, that's cinema.

If you want to check out a live, fullscreen version, or (god forbid) take a look at the actual code, it's available on OpenProcessing!

Also consider visiting @sableRaph on Twitter and joining his Discord server, where the Weekly Creative Coding Challenge is run.