Why does dappled light look like that?

Last summer I found myself looking at some dappled light under a tree. I realized that I didn't really know why it looks the way it looks, made up of a bunch of large, crisp circles. As a Graphics Person™, knowing why light does what it does is a point of pride, so I read up a bit. Now, almost a full year later (the first time in a long while that I have both time and energy at once), I can explain!

If you don't want a full answer, the short answer is that the circles are images of the sun from a bunch of pinhole cameras. But if you are interested, I'll explain it further below.

Hard shadows, soft shadows

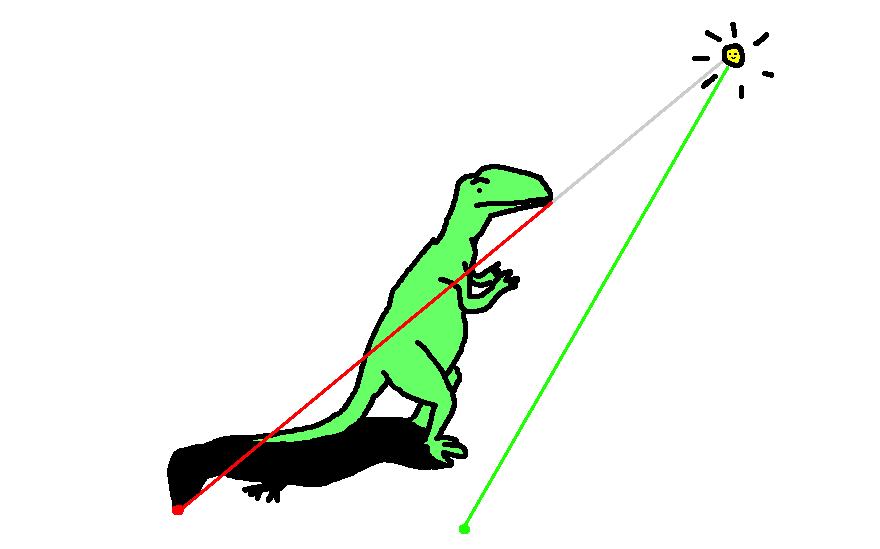

Let's quickly go back to basics. How does one end up with a shadow in the first place? Well, light moves in a straight line. If you can draw a straight, uninterrupted line from a surface to a light source (green below), then the surface should be lit at that point. If it hits something (red below), then that point on the surface is in shadow. The resulting shadow ends up forming the silhouette of the object blocking the light source.

If this were the full picture, all shadows would have sharp edges, since this straight line test tells us that something is either in shadow or not in shadow, and nothing in between. But soft shadows are a thing, so where do those come from?

Well, real life light sources tend not to be single points that you can either see all of or see none of. If the object takes up some amount of area in your field of view, you are able to have a partial view of the light source. How much shadow a point on a surface receives depends on how complete a view of the full light source it gets. A full view receives full light; a completely blocked view is fully in shadow; a partially occluded view is only slightly shadowed. The transition from having a completely clear view to having a completely obstructed view is what produces the smoothness in the shadow edge.

The bigger the area of the light, the more likely it is that surfaces will be able to see some of the light source. This is why, when taking portraits, photographers like to use big umbrellas to bounce light onto you: compared to the tiny area of a camera-mounted flash, which will produce hard shadows, the large, diffused area of the umbrella will produce softer, more appealing shadows.

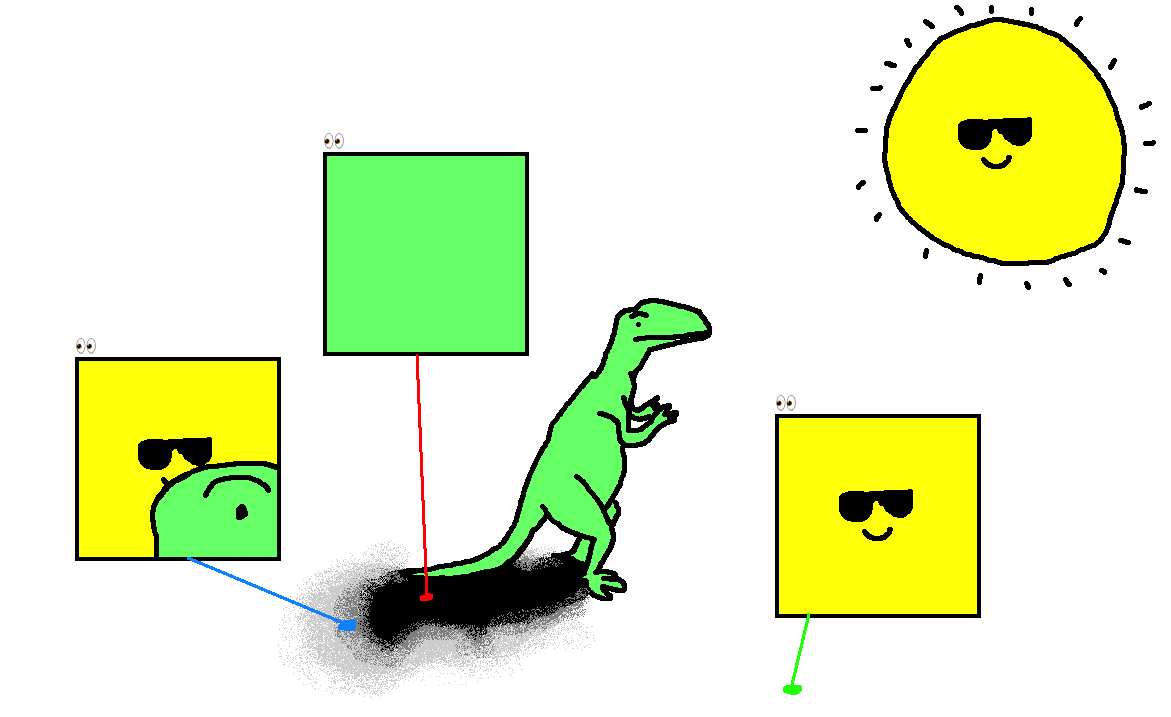

Here's a render of how changing the light area affects the softness of the shadow. Please excuse my poor attempts at adjusting exposure as the light size changes.

Indirect lighting also produces soft shadows. Light doesn't always stop when it hits something: some photons might be absorbed, but others bounce around. Even if your light source is tiny, if it bounces around a room before hitting you, it effectively turns the whole room into a large-area light source (albeit a dimmer one.) Pointing a lamp at the wall instead of directly at you is a low-cost way of getting softer lighting on you in your Zoom calls by turning your wall into a big ol' (indirect) light.

Pinhole cameras

Dappled light confused me initially because it isn't producing a clear silhouette of the leaves occluding the sun, but it also wasn't blurred in the way that soft shadows are. Instead, it's got circles everywhere. What's going on there?

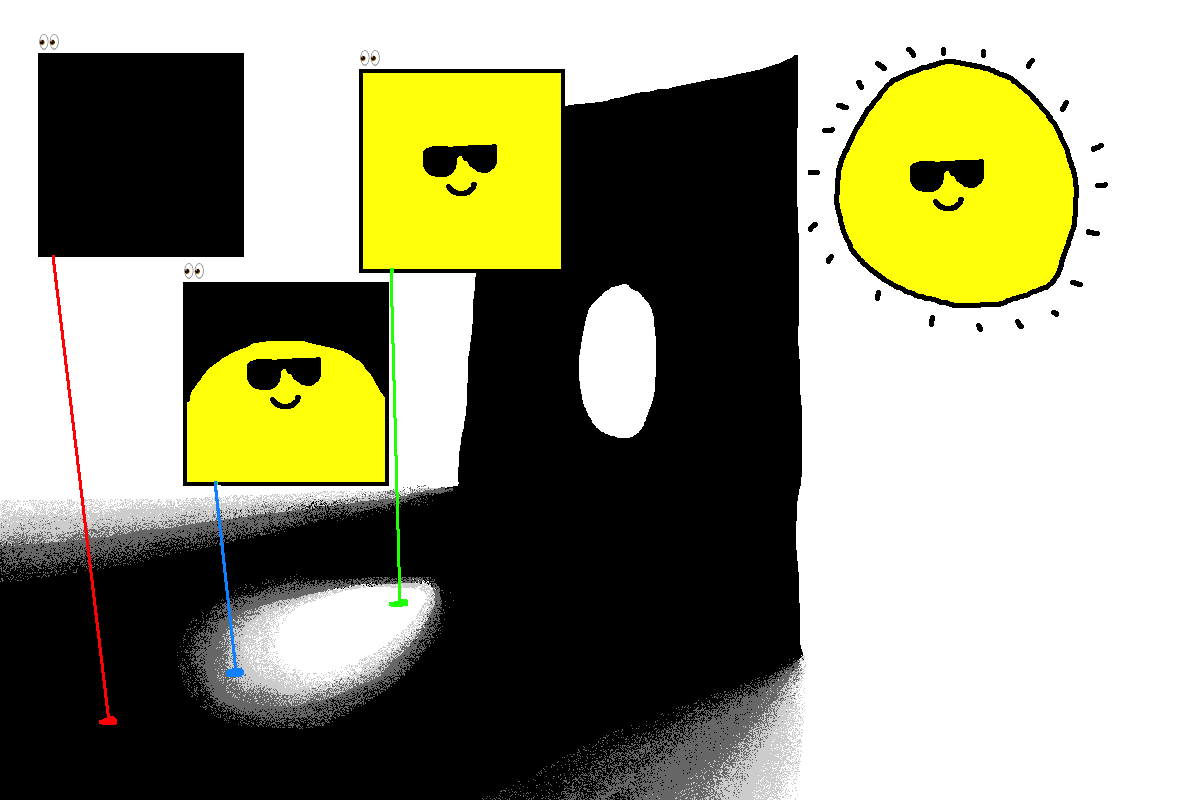

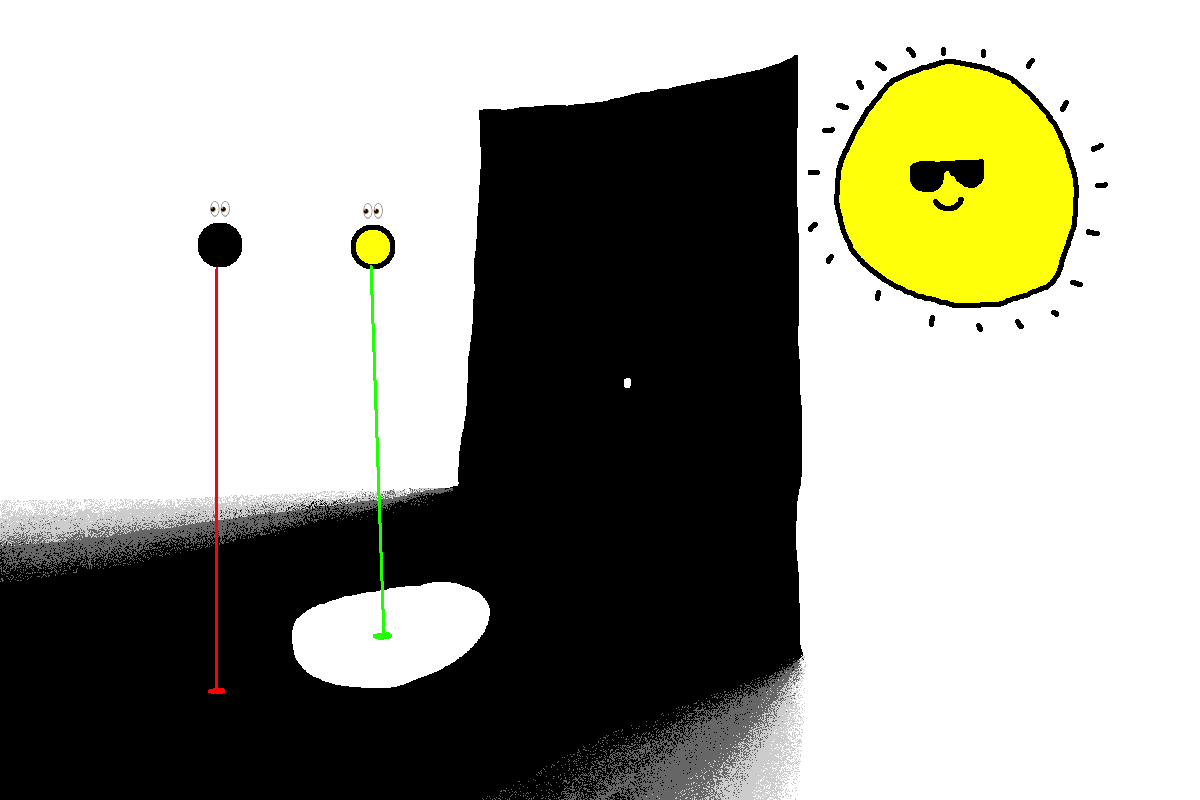

Let's think first about what happens if your shadow is coming from something that only lets in a tiny circle of light. At first, this looks like the same soft shadows from before.

Let's keep shrinking the hole until it's so small that it's effectively impossible to have a partial view of the light source, because the view itself is so tiny. Now, we get a hard edge again. This is what we call a pinhole.

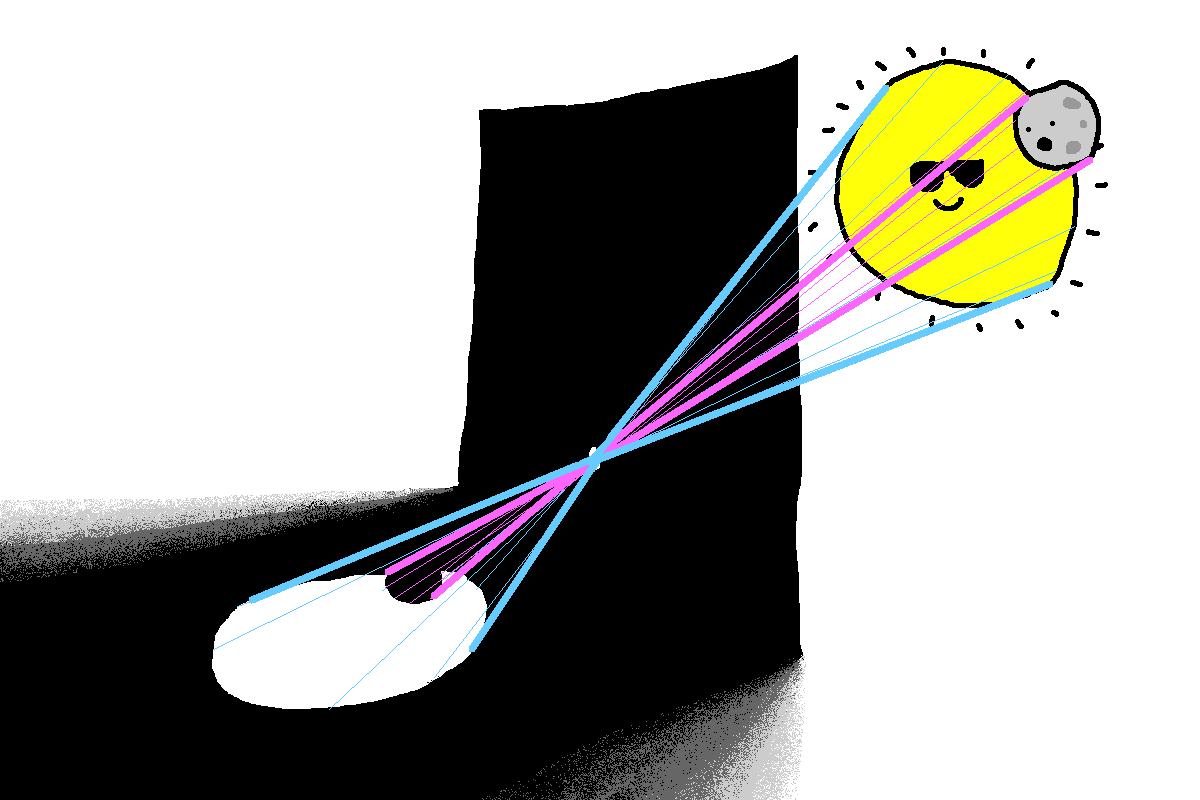

The shape of the light on the ground is a circle, but that isn't because the hole is a circle: remember, the hole is so small that its shape is effectively irrelevant. The shape is actually the shape of the light source itself. Every ray of light that makes it to the ground has to go through that tiny pinhole opening. If you draw lines from the edges of the light source through the pinhole, and then extend those lines all the way to the ground, you get the (inverted) shape of the light source on the ground.

Imagine we do this experiment again with an object in front of the light source, making it no longer be a perfect circle. The shape on the ground mirrors that new occluded silhouette. This happens in real life, for example, during solar eclipses, so if you don't have special sunglasses, you can look at an eclipse by constructing a pinhole and observing the shape of the light that comes through.

Here's a render of what it looks like as you change the size of the hole. As it approaches a pinhole, the shape of the light source gets clearer, and a small bite out of the circle due to the occluding object becomes visible.

How leaves make pinholes

So, finally, here's where dappled light fits in.

There are just so many layers of leaves on trees that when you look through them, they block most light, and only let through tiny pockets. Pockets tiny enough that they are effectively pinholes. So every circle of light on the ground beneath a tree is actually the image of the sun coming through a pinhole gap between leaves.