A decade in the industry

I realized recently that 2025 marks 10 years since my first actual job programming. Next year, I turn 30. I won't claim to call that old but I also don't think I can claim to be new to all this at this point either. I now find myself sometimes in the position of mentoring other, younger people into the industry too. I figured I'd reflect a bit on how the last decade has gone.

I see my own journey as one initiated through access to technology that I could use as a creative medium. A lot has changed since then, with technology getting refined but corporatized and declawed, but also with a strong undercurrent of new creative tools to take up the torch. I believe in code as a creative medium and one of my goals is to give back and push that medium forward.

The Before Times

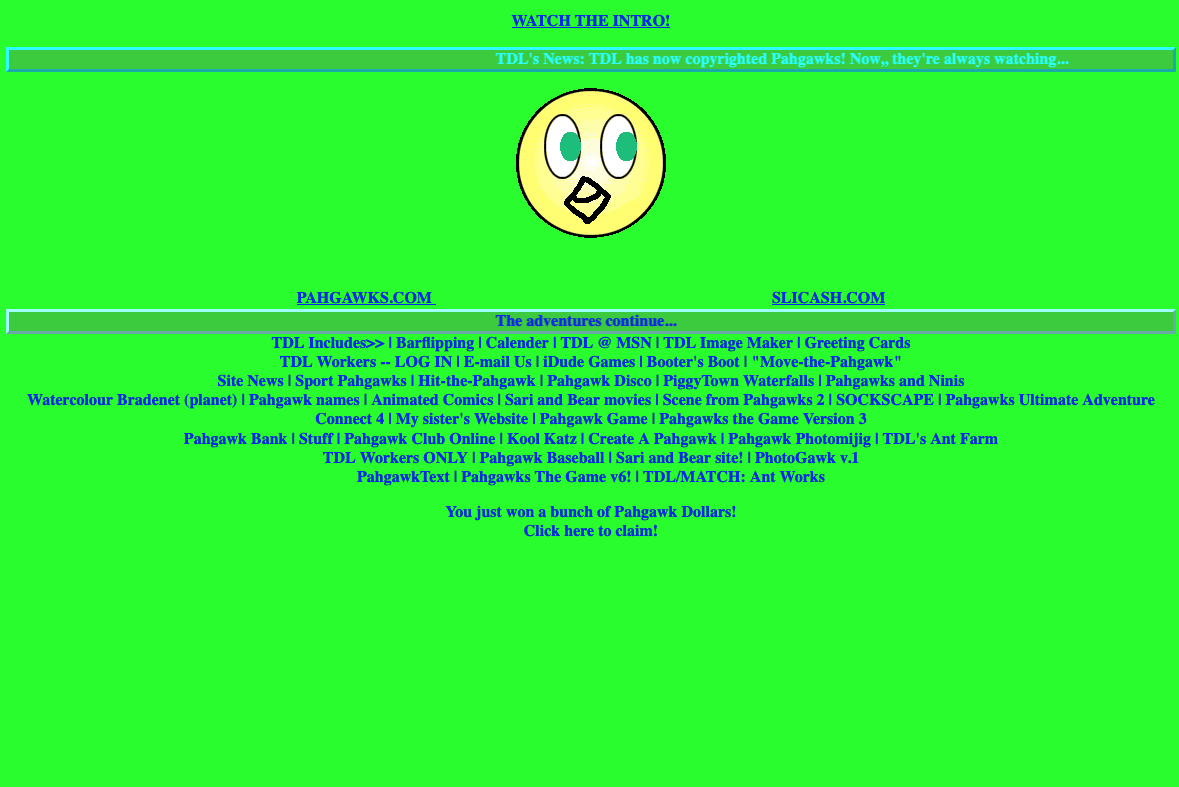

I've been programming for a long time, since way before my first programming job. My parents made the controversial move of putting a computer in my room when I was quite young, possibly 6 years old if I recall correctly (it's young enough that it's kinda hard to recall correctly!) The possibilities felt endless, so long as I put in the time to learn. A summer camp I took before the third grade gave me some space on Carleton University's web servers to host a little website. It was my own corner of the internet! The idea that you could make a little experience for people, and then they could go see it from anywhere, was incredibly appealing.

My website in 2006ish. Yes, that's the colour scheme. There are two marquees with beveled edges. The eyes in the middle follow your cursor. There's even a fake scam ad at the bottom. 'TDL' stood for Tristan David Luka, some friends and I making things related to these bird characters called Pahgawks.

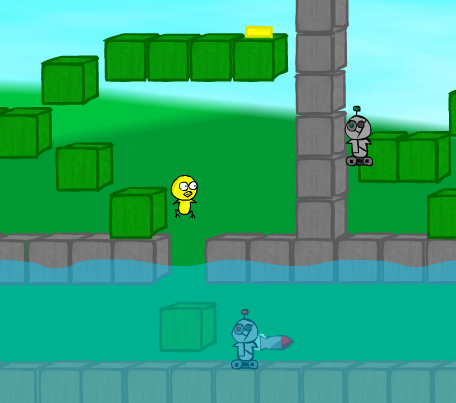

I made some animations in Flash. I scripted some buttons in Flash. I followed some game programming tutorials on Newgrounds. I animated characters for those games. I turned an if into a while to see what happened, and when my game froze and crashed, I got scared of while loops for another few years before learning them properly. The boundary between the art part and the code part was permeable.

I wasn't always on the path to becoming a programmer. For a long time though, it was actually just a side thing that I did because it was fun. The vast majority of my time and energy went into animation. I spent two summers competing in the Newgrounds Annual Tournament of Animation, where you made a new animated short every month while you remained in the bracket. I came in second place twice, which meant I ended up making a lot of animations. While I love the medium, I found the day-to-day work of animation to be a little too gruelling for me, especially in that volume. I find I enjoy it a lot more when it's just done as a hobby.

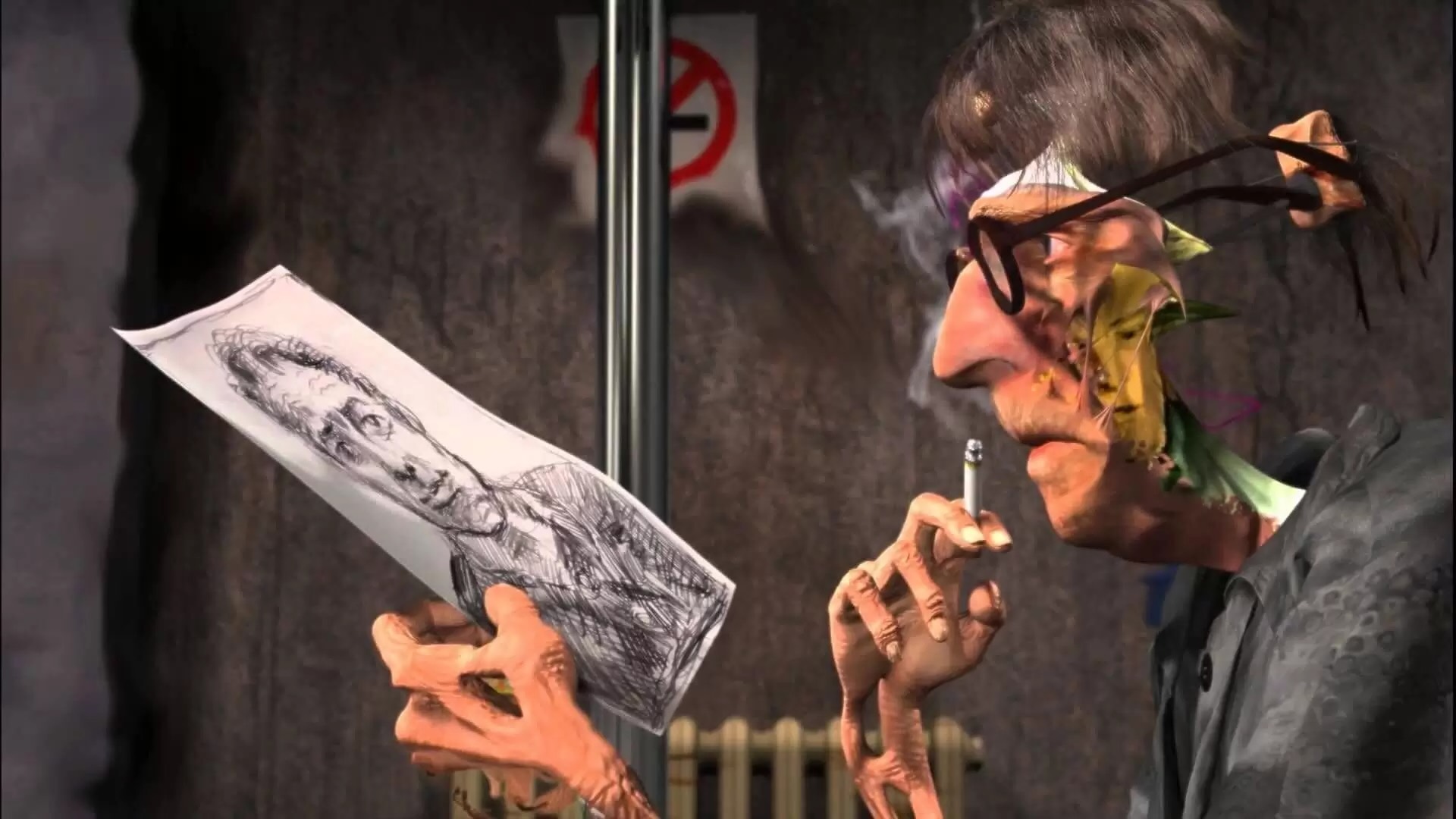

My head is still largely in the creative space though. In retrospect, two of the pivotal moments in my career were watching the special features on DVD. One was for the NFB film Ryan (2004) by Chris Landreth. They talked about how not only was creative filmmaking employed to Oscar-winning ends, but they also had to write new software to enable the vision for the film. Specifically, Landreth worked with Karan Singh to implement some new algorithms for hair rendering into Maya. This was mind-blowing. They were Canadian too!

Another was Pixar Shorts: A Short History (2007), which came on a DVD of all the Pixar shorts. It talks about the history of Pixar, and largely, how the technological and artistic developments were intertwined. Animators and engineers were working literally side by side in the office, and the works in progress each saw would influence the other. When Ed Catmull gave a talk at SIGGRAPH this year for the 30th anniversary of Toy Story, he mentioned again how ridiculous it is that art and technology are considered opposites, when combining them felt so natural to him. That was what I wanted for me, too.

That said, though, as I grew up, it felt a bit like I had to pick a lane.

Becoming a programmer

I thought at one point I wanted to make websites, as a medium that tangentially included all the things I liked. My dad pointed out that making websites was something I already did, and that it'd be worth exploring where else I could take those skills. He got me a book about Perl.

In high school I got paid to make a few websites, but just for my mom and my mom's artist friends. I'd made some little productivity tools for myself in Flash and got myself a free developer copy of the Blackberry Playbook (RIP, lmao) by porting it to their platform. My website grew to resemble the structure of this current one, and had a Perl system I wrote to string it together. My high school CS and physics teacher said his alumni got jobs by knowing SQL, so I learned that and made a bad joke database. Flash was declining, so I learned JavaScript. I made a graphing calculator and symbolic differentiator that I was proud of.

Picking a university program is generally the point where you're expected to make (at least the first attempt at) a decision about what you Want To Do. By the twelfth grade, programming seemed to be a more general path than just making websites, and I found I did enjoy the work a lot. So I applied only to software and computer engineering programs. My grandfather, who was himself an engineering professor, took me to an open house at the University of Waterloo for people who had been admitted to their software engineering program. They had us solve some little programming puzzles in teams, and it was a lot of fun. That sealed the deal for me.

The summer after grade 12, knowing where I'd be going, I wanted to try getting a Real Programming job. I wrote a resume. I got my uncle, who runs his own business, to review it. I sent it to a bunch of places. I heard nothing back from anyone.

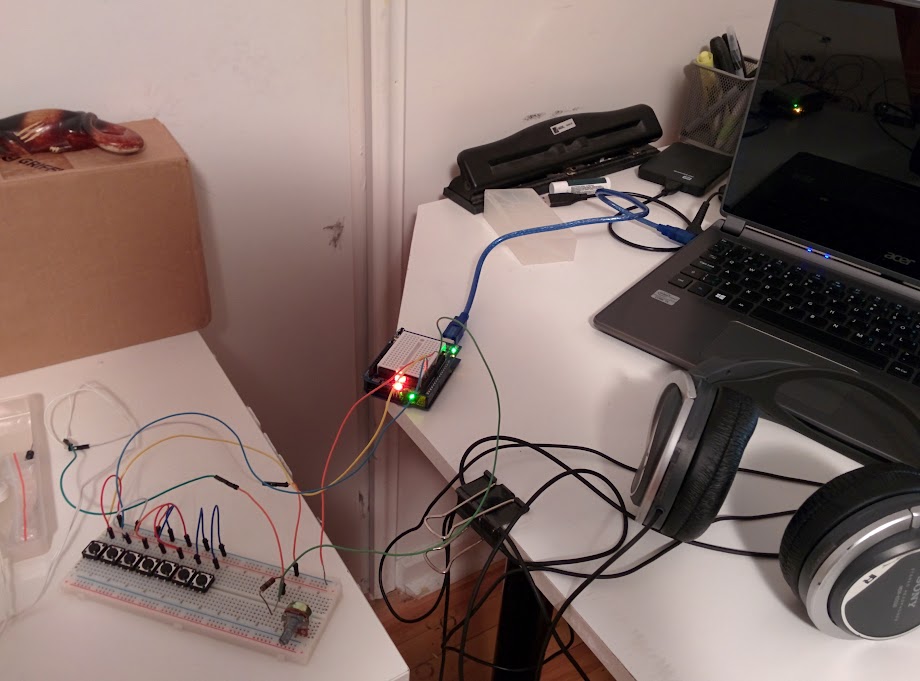

It happens. I tried to dedicate that summer to learning instead. A friend of mine lent me an Arduino. Another friend, a year older and already at Waterloo, had me help on a programming project of hers, and got me to fly to Silicon Valley for a hackathon. I made do.

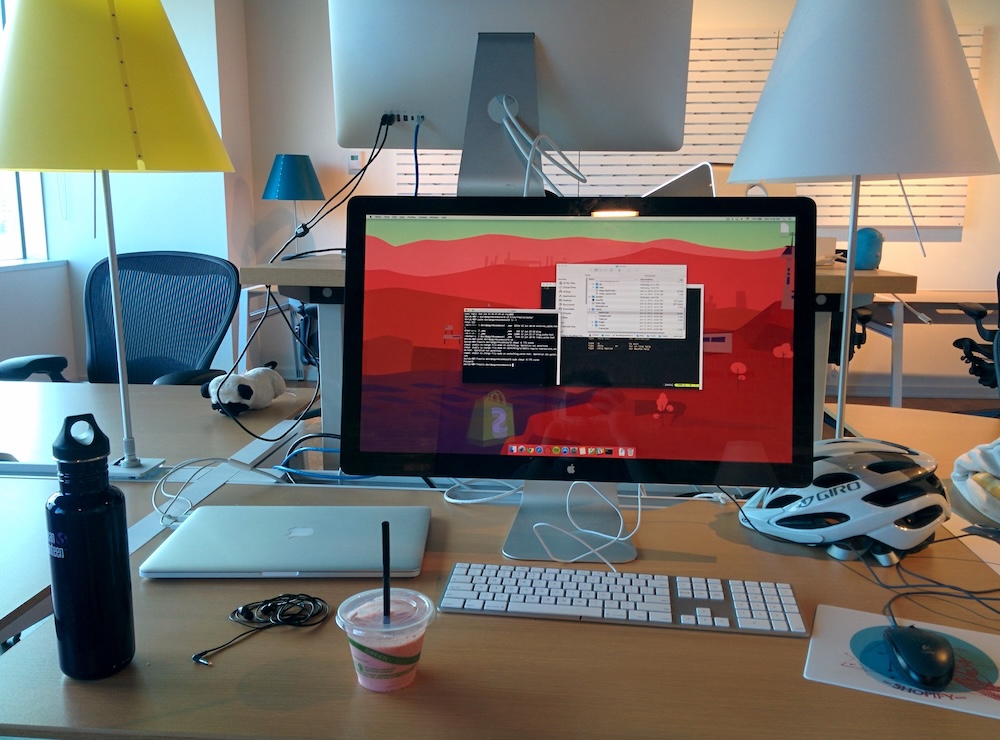

The next summer, after completing my first year at Waterloo, I got a summer internship at Shopify in my hometown of Ottawa. Compared to before, getting a job was a lot less frustrating. I wasn't drowning in job offers, but companies would actually tell me no instead of just not replying! And I did actually have a whole two offers! And thus my formal Entry Into The Industry commenced.

The tech industry, as I entered it

I think I grew up during a period of change in the tech industry. A few big companies were becoming more and more dominant, with smaller sites disappearing. Instead of finding lots of cool little websites on StumbleUpon, why not do everything on Facebook? Even in the code, the medium of it all, a corporatization was happening.

When I started, Ruby on Rails was finishing up being the main cool thing. It had a fully-batteries-included monolithic model, where you had everything you needed ready to go. It was expressive to write in, at the cost of some code being a little magical. There was a notable move in the opposite direction from all that, which often came from the very places that started out embracing Rails. This may have been in response to learnings from scaling Rails up in terms of both users and developers. New services were getting built in the relatively new language Go, with strong types, C-like control, tools for concurrency from the get go, and generally one right way to write things. Shopify, then and now one of the big users of Rails, had started making new services in Go. That's actually what I worked on while I was there: a query engine for merchants' data, written in Go. Everywhere I'd work that had rails, the yin of Rails would come alongside the yang of Go. Go is great at what it sets out to do, but the goals had changed.

Flash was previously one of the most accessible tools for creating new interactive experiences (in terms of developer experience, if not cost, but piracy was rampant anyway.) Although I had learned to program in Flash, Flash was all but dead by the time I started work. The writing had been on the wall for a while, with the mortal blow being dealt five years earlier. This had been obvious even when I was in high school, so I had learned JavaScript as the apparent way forward for the web. That proved to be a good bet.

There were a number of efforts underway to professionalize JavaScript. Node.js was the rage. The ES6 spec just came out, which you could use if you set up a build system instead of just hand-writing files. In school, everyone was talking about JavaScript frameworks. There was a lot of energy but not a clearly dominant path forward. People came across Ember.js and Backbone.js on slightly older codebases. Newer codebases might be using Angular or React. There were some new, not-quite-battle-tested ideas that were just starting, like, maybe WebComponents could replace frameworks? Or, maybe you could run the same code on mobile too if you used a special system like React Native or Dart + Flutter? It felt like everyone had to have an opinion. Everyone took a side. The endless discussion was, frankly, exhausting. I hoped that just knowing JavaScript really well would let me jump into whatever system ran on top of it easily enough. I did end up using React more than the rest though—the React component system clicked with me well enough that I'd use it for personal use when I needed something a little more organized than JS on its own. That seemed to work out for me. Another lucky bet.

There were still things moving against the grain, just outside of the industry spotlight. Processing had been around for a while as a common way to get into programming via graphics. I had encountered it briefly in Artengine workshops in Ottawa. While it started as a web tool, with Java applets being one of the original ways to do interactive stuff on the web, that had ceased to be the case for a while. When HTML 5 introduced the <canvas> element, new opportunities opened up. p5.js started in 2013 as an addition to the Processing family, built again for the web on this new technology. Both projects are aggressively non-corporate, emphasizing what you as an individual (who might even be new to code!) can accomplish.

Finding my way (back) to graphics

Waterloo has you alternate between school and work terms. That makes a total of six work terms, and six opportunities to do real work and get different perspectives before truly being set loose into the world. I did different things each time, and I certainly learned a lot from each place. It took me a number of them to realize that, while I tried to contribute every time, it would take more active involvement on my part if I wanted to end up in a spot where I was doing both code and art.

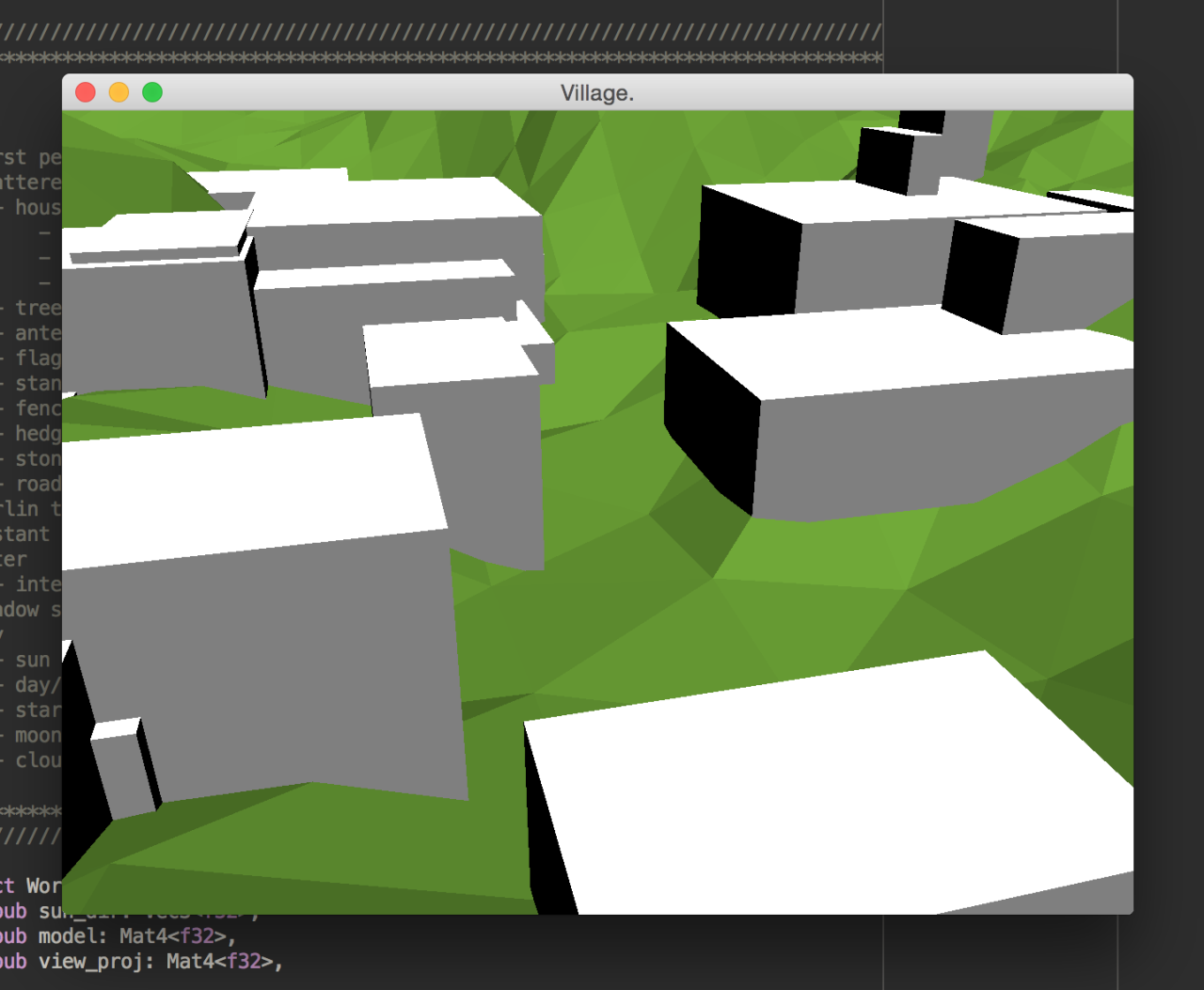

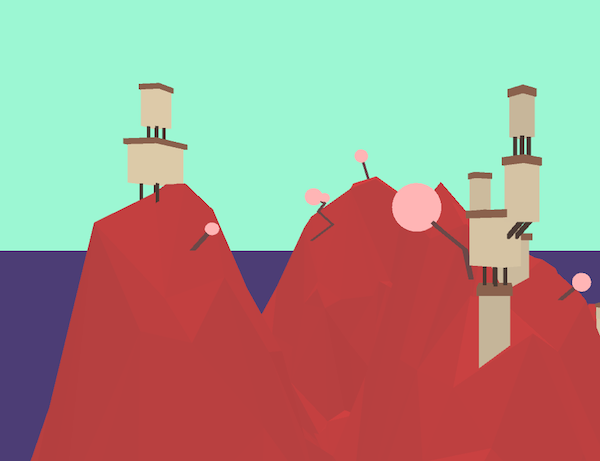

It took a while to get to a point where I felt like I had something meaningful to contribute. I heard about the book Ray Tracing In One Weekend (now free online!) which I followed and used to create a Swift raytracer. The most helpful thing about that book/series is that it gives you the language to talk about current rendering research, while still being incredibly approachable. But on the whole, I saw the most opportunity after learning about generative art. I stumbled upon Brendan Zabarauskas's Voyager3 project on Tumblr, creating landscapes and villages from code. The rendering itself is far from fancy; in fact, its minimal, concept art sketch style is part of the appeal. I loved the idea that you could define the rules of a system, and then it could grow into something bigger than you imagined. It could surprise you. I started reading about things like generative grammars and L systems. I made my own generative landscapes inspired by the 2D concept sketches from Voyager3, and later, some in 3D, too. These were all done in Processing, as that seemed to be the fastest way to get up and running in both 2D and 3D.

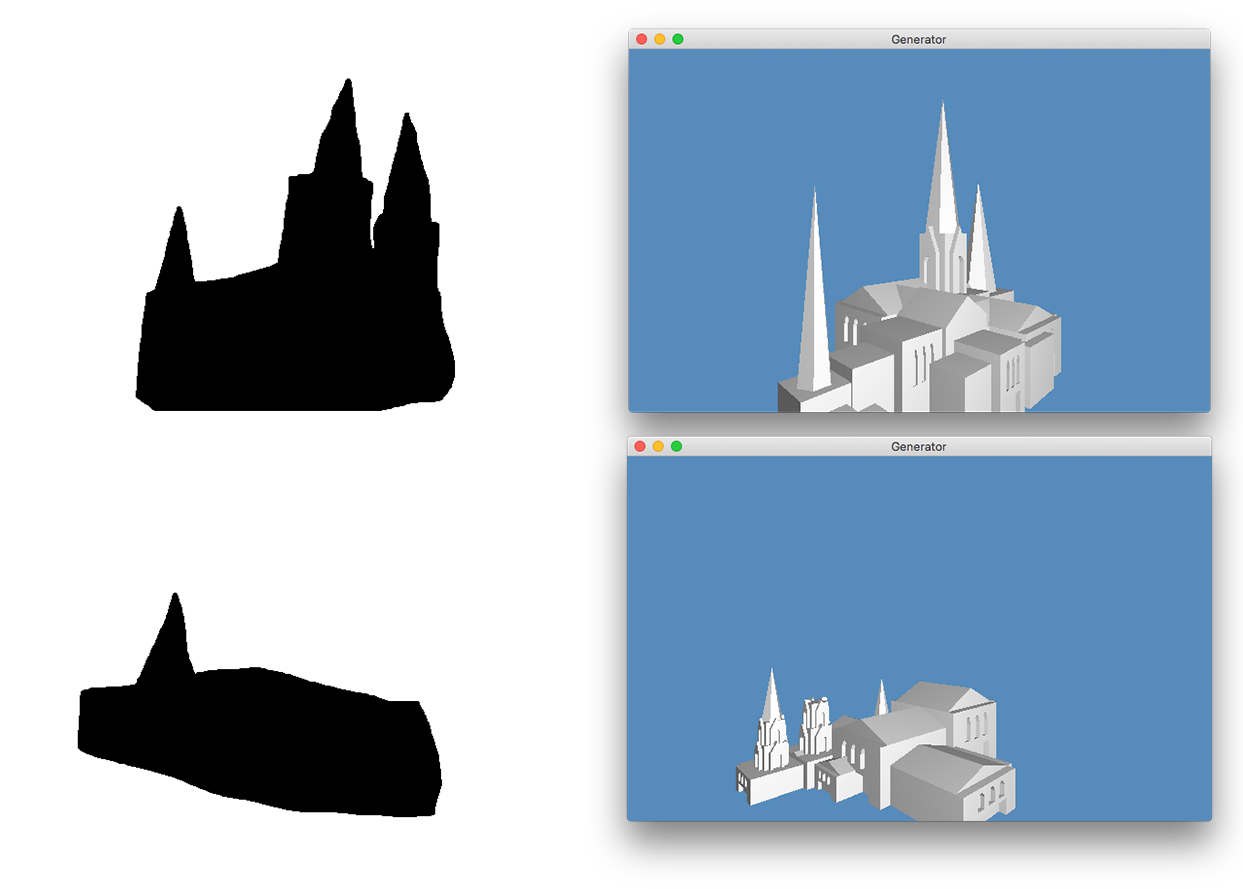

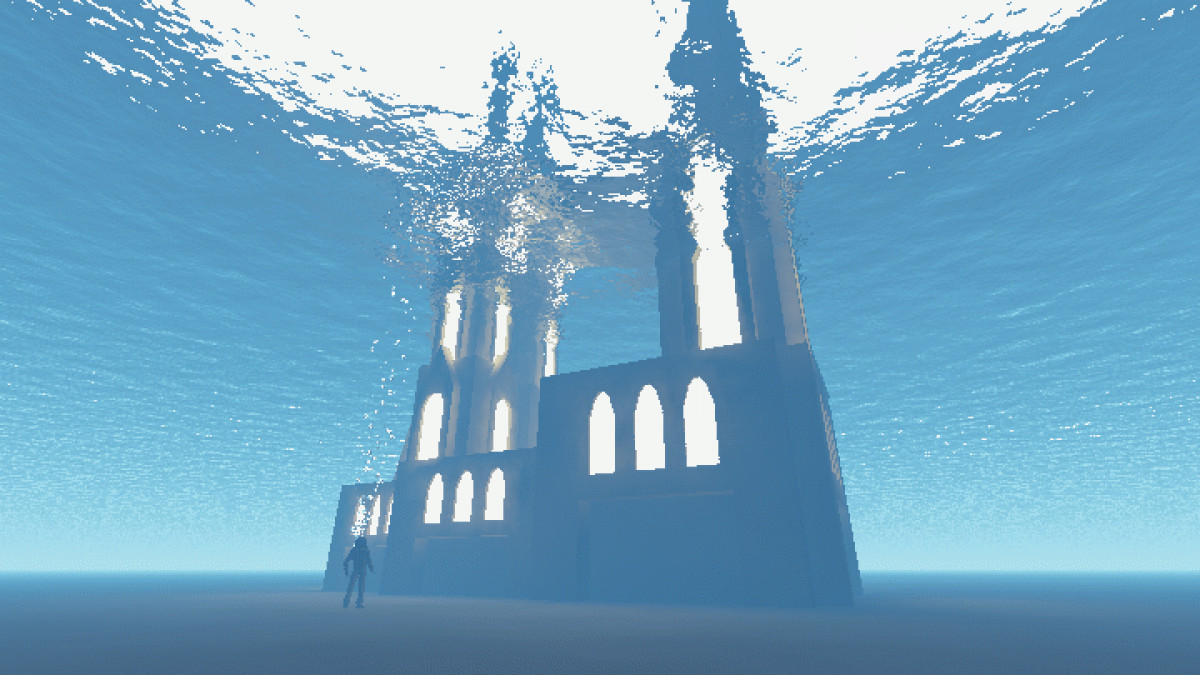

In 2018, for computer graphics class at Waterloo, the final assignment was very open ended, and I took the opportunity to try out the Pixar technique. I created a short animation rendered entirely in software I wrote myself. After implementing the rendering fundamentals and ticking the usual assignment boxes, there was room to explore things closer to the bleeding edge in one way or another. I had stumbled upon a recent SIGGRAPH paper about controlling the output of generative models: rather than just generating and regenerating and looking for something cool, you could try to find output that optimized some objective, such as a target silhouette. This was the kind of tech that seemed the coolest to me: it had the potential to give me a new creative tool to sculpt outputs I couldn't feasibly create manually. I implemented the algorithms in the paper and used them, hoping to create a surreal, detailed cathedral that I would have trouble making on my own. It kinda worked, but was a little too slow and hard to control to really get to what I was after. But the result looked decent enough.

At Waterloo, you have to make a fourth-year engineering design project, kind of like an undergrad thesis. I wanted to push myself firmly into the realm of doing something new for generative art and do some legit computer science research. I struggled with figuring out exactly what to do though. I saw a lot of cool ideas out in the wild that were only being tested out by a few people. The problem, it seemed, was mostly that all these ideas required custom from-scratch code, lived squarely in code as a medium without letting you sketch the parts that are more easily sketched, and were too slow and uncontrolled to be worth using for artists. I tried to come up with project ideas to deal with that. I tried to design a more declarative way of making 2D fractals. I tried to design APIs to make it easier to code 3D procedural models. Unfortunately those weren't clear fits for a research paper. How do you prove that your design actually makes an impact on usability? Maybe some user studies or something. Hard for some undergrads to undertake, anyway.

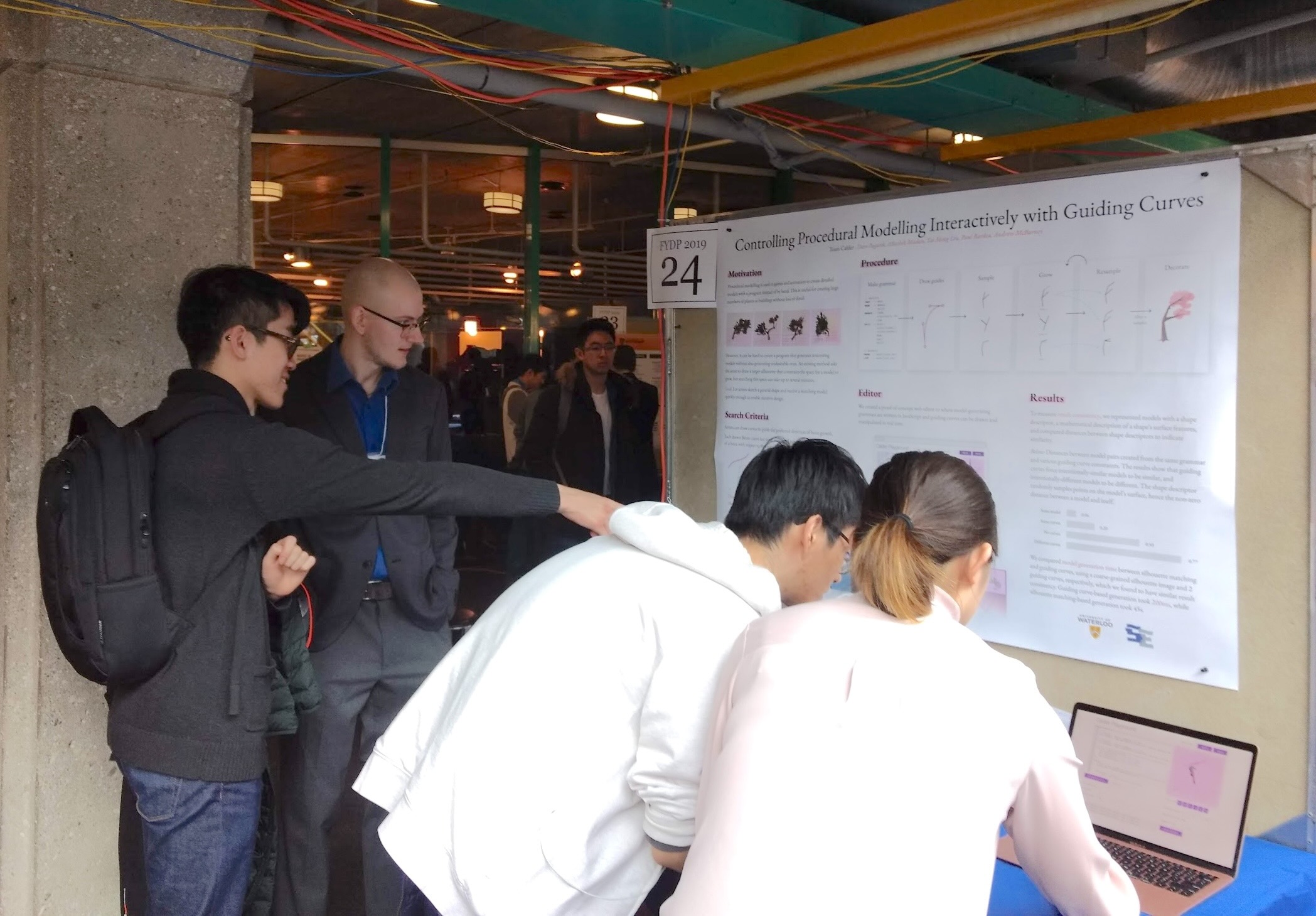

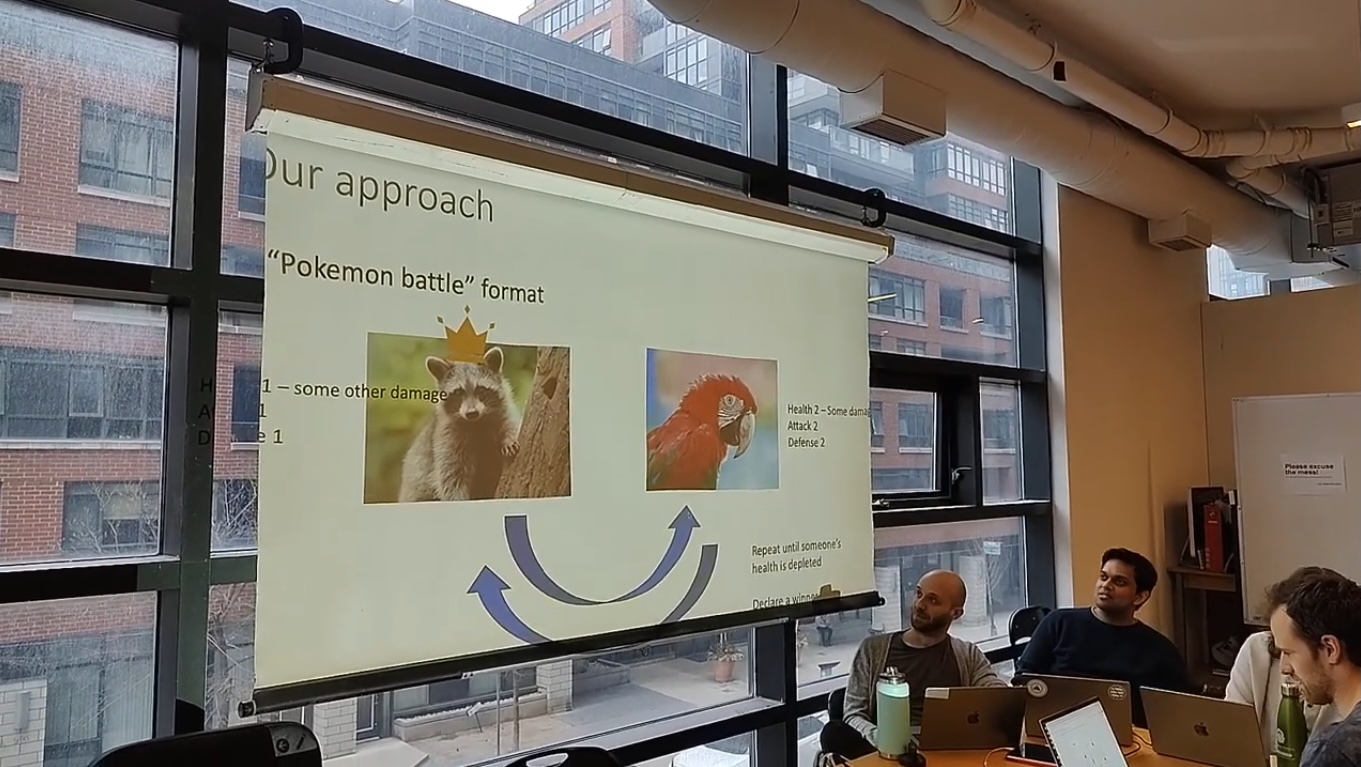

Eventually, we identified a much clearer, smaller-scoped problem to tackle. The constrained procedural generation I tried before was too slow and the controls were awkward to work with. Could we design something that was looser, easier to create, and faster to run? We ended up doing so using guiding curves instead of silhouettes, and published a paper on it. A journal thought the approach was worth something!

We went to present it at Graphics Interface. Most talks in this setting define a technical problem and then explain an algorithm to deal with it. We did do that, but arguably our algorithm wasn't the most important part—it was already so specific, you probably couldn't branch off of it and get new research. For me, the goal was to try to get generative design to a point where more people can use it. To me at least, it made our talk feel a tad out of place among the other research, and I think my blog post about it does a better job getting those ideas across than the paper. But because the algorithm only lived in a proof-of-concept editor for a custom framework purpose-built for this (with remnants of our earlier design ideas littered half-thought-out throughout), we didn't actually gain any artists either. Integrations matter. In contrast, the new tech in Ryan was built right into Maya, and its implementation was paired with a project that immediately made use of those new ideas.

I could have continued into industry right out of school, but didn't. I maybe had found my kind of people working at Figma in my last internship, but I felt that I had more to learn, and possibly more to contribute in other creative fields (I appreciate UI design, but I wouldn't say that I'm a UI designer myself.) I went to UBC to pursue a master's degree in computer graphics and see if I could do more working on tools for artists.

My time at UBC was complicated for me. I was in a research group that was doing the exact kind of thing I was interested in, making algorithms to help with fabrication of garments and CNC milled wood, for creating 3D content, and for understanding sketches better. I worked on an algorithm to figure out the underlying curve that is suggested by overdrawn sketchy lines. That could be really useful for editing sketches: select a group of strokes, and get a single curve you can use to manipulate the whole group. However, like before, it never really made its way to real artists. This time the problem was that it never ran quite fast enough to work on consumer hardware, it relied on an expensive licensed mixed quadratic programming solver, and was too complicated conceptually to be feasible to reimplement on something else. It definitely wasn't used by artists because the toy implementation also only used a custom data format used in the lab. I implemented enough of an artistic tool using the algorithm to make the figure below, but never pushed it further. I was burnt out from the one-two punch of the lab's crazy work schedules and then from the covid chaos that hit halfway through.

However, as the burnout set in, I understood I needed to do something else to keep my sanity and finish the paper. I finished an animation I had started that same final summer after high school. I got back into making small creative code sketches. I collaborated with my mom on some code and some music for some art. And then someone I used to work with in my second internship reached out: he was looking for a graphics programmer to help make an animation tool leveraging creative code for the visuals. This sounded like a great fit: working on artist tools but starting at directly at the tool this time, and working with people I've enjoyed collaborating with before? Great! I started working on that on the side while finishing up my paper and degree.

That project started off in p5.js. Because the visuals are made with code, they could respond to inputs in a way that something manually made in, say, After Effects couldn't without high effort. Moreover, in addition to being a way to sketch with code on the web, p5.js is often used to teach CS concepts because of its accessible design. The idea for using it in this animation tool was that the easier it was to create coded visuals, the more of them and the larger variety we could get. It's freeing to be able to just write a sketch to make a new component when necessary. The adaptability of a sketch makes them pretty fun to play around with too.

This lead me to get more and more involved with the p5.js project and its community. It started with fixing some bugs we noticed in animated gif playback when adding support into our tool. Then it was increasing the performance of image tinting, something I ran into with that project with my mom. As our ambitions for our tool evolved, it was becoming clear that we'd need to build it primarily in WebGL to be scalable, and while p5 had support for that, it didn't have quite enough tools to achieve what we wanted, so we added support for framebuffers, masking, high-fidelity lines, and easier retained geometry.

It's at the point now where we have our bases covered in our tool and in p5. For our tool, it took a number of years, but Butter is something you can sign up for and use right now, and it grew to be a near-full browser-based video editor as a backbone for the more unique creative code stuff. On the p5 side, WebGL mode grew to be a stable and productive backbone for Butter, and also for many creative coders. I grew to be one of the maintainers of p5.js, and got the opportunity to meet lots of amazing people in the open source arts community.

With a solid foundation like that, it's possible again to try to push the limits and do something truly new. Compared to my previous attempts, though, the two areas I work on—Butter and p5—are used by artists. New things actually have a fighting chance of gaining adoption. At Butter, we've only just started to see the benefits of having every component be written as an independent p5 sketch, and we're going to slowly open that up to more developers soon to lean into that. For p5, we've started trying to crack open previously inaccessible aspects of graphics programming, and have built a way to create shaders using JavaScript, which feels similar to building a regular p5 sketch. I hope both of these things will continue to grow and open up new creative possibilities for people.

Some reflection

I didn't realize it at the time, but I came of age in a golden era of sorts. The times were changing, but I learned a lot when it was still normal for a website to be like one file. Tech was still largely exciting and hadn't quite tipped the cultural scales towards being mostly scary. If I started five years earlier, I'd have still been feeling the post-2008 slump. If I started five years later, I'd be slapped with a messy transition to online covid school and then whatever it is AI is doing to upturn the industry. I started in a time of excess, where companies were excited to invest in junior developers and train them up. I don't think that's quite true any more in 2025.

Learning JavaScript proved a good career bet. In zero of my six internships could I avoid JavaScript, even in ones that had nothing frontend-related in the job descriptions. When working on a mobile app for muscle-tracking athletic wear, I added some support for executing snippets of JavaScript math to make it easier to test out new calculations. When working on self-driving cars, the code I wrote that lived the longest after I left was a WebGL path planning visualizer. OK, at Google when working on embedded machine learning, the only JavaScript I wrote was for their weekly code golf game. But hey, 1/6 is still pretty low! Browsers have advanced to a point where you again don't need a big build system to write interactive web stuff: modern JavaScript is pretty decent, and you don't have to transpile it any more to write in it. The technology of the open web is still a very good bet.

The industry as a whole is kind of losing its big corporate approach to software, but only because it seems to be deciding that everyone wants to be able to flirt with their search engine, ask their airline's chatbot for help with their physics homework, and interface with everything like it's a text adventure out of the 1970s. AI is certainly changing our relationship with software, but I'm not sure its current form will be sustainable.

At least people at large have woken up to the idea that the tech industry may not always have their best interests in mind. We no longer have a monoculture, and there are lots of smaller communities out there with people going against the grain, pursuing interesting ideas. While mainstream Big Tech gets less interesting, access to technology has universally gone way up. While making fun games or graphics or websites used to be an uncommon, niche activity, it's easier than ever to get into. Even phones now have a decently powerful GPU in them. Naturally, there are a lot of creative people out there making good use of those resources. The trouble is just finding those people and surrounding yourself with them.

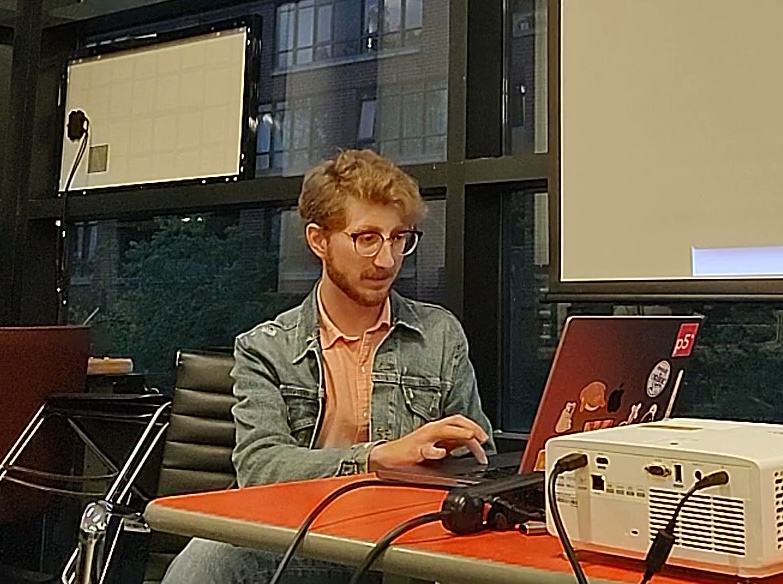

Bluesky and Mastodon aren't perfect but are more fun than the mess that preceded it. The p5.js Discord server is friendly and encouraging, and the Birb's Nest Discord is that too, plus it runs weekly graphics prompts to inspire you. Here in Toronto, I started a little community of creative technologists who meet up monthly to share what we've been working on. Inter/Access, a maker space and gallery, reached out and offered to let us meet up in their building. They're great people who are motivating to be around.

My best advice for young people right now, dealing with our present uncertain times, is to try to find that community. Or, if it doesn't exist yet around you, try to start it yourself!

The people you know expose you to all kinds of opportunities. I started tinkering with code in Flash thanks to an encouraging and creative community on Newgrounds. Arts organizations in Ottawa introduced me to things like Processing. My current startup came about because of people I used to work with. Working with p5.js has connected me to so many creative people who are doing all kinds of interesting work.

I hope I can eventually create similar opportunities for the people in my community.